Business trailblazers set the agenda on the future of work – from dealing with disruption to an entrepreneurial workforce

HR leaders and world-leading faculty gathered at the Science Museum in London to discuss challenges facing organisations. London Business School’s (LBS) HR Strategy Forum, in its sixth year, provoked a rethink in best-practice.

Preparing an on-demand workforce

Tammy Erickson, Adjunct Professor of Organisational Behaviour at LBS found inspiration in some of the inventions on display. She referenced the British innovator Henry Maudslay, who invented the first industrially practical screw-cutting lathe in 1800, which standardised the making of screws. She said: “Before the lathe, screws were made by self-employed screw-makers. They were paid for the product.”

Drawing a parallel with the nature of work before the Industrial Revolution, she said: “I predict that we will go back to a time where workers do contingent work, on a flexible basis. You will hire workers when you need their specific skills at a particular point in time.” She suggested that the key HR function of the future will be to set up a network that can be tapped as and when a company needs it.

“You won't have to own people. You will be able to rent them. Now you need to start concentrating on getting the right people in the right place to do the right work at the right time.”

Dealing with disruption

Costas Markides, Professor of Strategy and Entrepreneurship at LBS, reported that the average 18-year-old now expects to have 10–14 jobs by the age of 40. “Think of the implications,” he said. “The challenge is not how to attract the best talent anymore, it’s how to retain and energise people so they don't leave.”

Mobile technology, he added, has changed people’s habits and attitudes. “Your customers and employees are less attentive, less loyal, more informed, less patient, more demanding and more connected.” As such, companies have radically transformed how they manage their employees, how they serve their customers and how they compete with each other. But, he said, “You haven’t seen anything yet”. Radical new disruptions are on the way –including artificial intelligence, virtual reality and machine learning.

In order for organisations to deal with the next wave of disruption, people – from leaders to front-line workers – must stop thinking of disruption as a threat. “You need to frame disruption as both a threat and an opportunity,” he said. In addition, you can prepare your organisation for continuous transformation in three ways, he added.

- 1. Institutionalise the attitudes and behaviours that will enhance your agility

- 2. Develop the environment that will support and encourage these behaviours

- 3. Make the need for changing these behaviours personal and emotional.

The future of work

So far, the technological developments that we have experienced in the fourth industrial revolution have augmented non-routine, analytical work, said Lynda Gratton, Professor of Management Practice at LBS. “But it’s a very different picture for other types of work such as routine, analytical and manual tasks which have seen technology replace people,” she added.

Referencing data from the World Bank she said, “There are two major losers. The global poor and the traditional middle class.”

“This is the first decade that when children in Europe and the US were asked ‘Do you think you'll do better than your parents?’ they answered ‘No’. And where does that leave us?”

In her book The Shift, Professor Gratton suggested that the contract between the individual and the organisation is beginning to change. “The old contract was ‘I work to make money to buy stuff that makes me happy’. This will change to become ‘I work to make me happy’.

“Whilst your company might already say that as a philosophy, I don't see many companies actually realising how profound the change of contract will be.”

The quest for an entrepreneurial edge

Gary Hamel, Visiting Professor of Strategy and Entrepreneurship at LBS suggested that bureaucracy was sapping human potential and emphasised the need for organisations to gain an entrepreneurial edge.

“Too many companies live in fear of being Uberised. They worry their tradition-bound organisations are too slow to out-manoeuvre start-ups.” He said that their anxiety was justified as the newcomers were typically the first to embrace new technologies and wow their customers.

To activate a spirit of ingenuity, he said companies needed to commit to moving “from incremental to bold, from complex to simple, from bloated to lean and from coercive to free”.

While entrepreneurship and scale are often seen as incompatible, they can co-exist, he claimed. But only with a radical overhaul of “management as usual”. His vision of a ‘management 2.0’ world included organisations where everyone acted like the owner, leaders chosen by the led and a system where everyone reports directly to the customer.

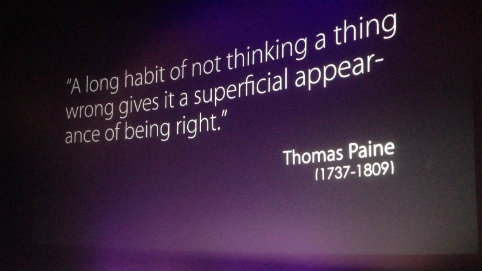

“It will take indignation to get there. Let’s get angry about it,” he said, ending with a quote by activist Thomas Paine to drive the idea home.