Among a recent package of headline-grabbing developments in the UK’s relationship with China, the People’s Bank of China has announced plans to issue short-term debt in the City of London.

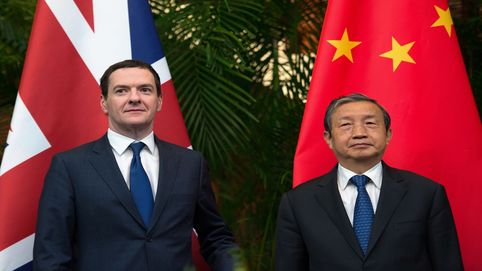

After talks in Beijing between George Osborne and Chinese vice premier Ma Kai, the Chancellor also revealed the launch of a “landmark feasibility study” into linking the countries’ stock markets, enabling Chinese and British shares to be traded in both territories.

The timing and wide-reaching implications of these measures raise some pressing questions.

Linda Yueh is Adjunct Professor of Economics, London Business School and author of several books including China's Growth: The Making of an Economic Superpower.

Writing recently on Forbes.com, she examined the potential gains and risks these landmark proposals pose for both countries.

City choice ‘no coincidence’

The People’s Bank of China’s plan to issue debt in London through renminbi bonds is a first outside of the country itself.

From the UK’s perspective, it marks a further step in the City’s drive to emerge as the major centre for renminbi trading outside Asia, and become China’s “bridge” to Western markets. It solidifies the Chancellor’s pledge to “stick together” with a Far East giant undergoing significant financial turbulence.

China’s stock market crash has spooked western investors. In August, the Shanghai market experienced an 8.5% slide on a single day, but Mr Osborne set about restoring positivity around China during his recent trip east.

“The choice of the UK is no accident,” says Linda Yueh. “Wooing China has been part of the UK’s strategy for some time.

“London dominates global foreign exchange trading but would find it hard to hold onto its position if the currency of the world’s second largest economy, and its biggest trader, wasn’t choosing the UK.”

China has been strategising the internationalisation of the renminbi for years and intends for it to eventually emerge as a global reserve currency. Linda Yueh believes this latest move carries little risk.

“There isn’t a great amount of risk in a central bank issuing bills since they, after all, control the money supply,” she said.

Interlinked trading

If the People’s Bank of China’s selection of London as a base for issuing currency is no coincidence, neither was the choice of the Shanghai Stock Exchange as a venue for Mr Osborne to announce his latest plans for a joined-up market.

Stuttering economic growth in China has done little to deter the Chancellor from his mission of strengthening political and commercial ties, most notably through the proposed linking of Chinese financial market – largely closed to foreign investors – and the UK’s.

Linking the markets would allow the UK to benefit from Chinese growth and offer support for its economic and financial reforms, while giving Chinese firms greater access to international finance, Mr Osborne claims.

But China recently revised down its 2014 growth figure from 7.4% to 7.3% - its weakest showing in nearly 25 years – while this year’s target is set at just 7%.

Linda Yueh says: “[This decision]… may breed more volatility. It’ll be interesting to see how far this progresses by the time the Chinese President visits the UK later this month.

“So far, the dramatic double digit falls in Chinese stocks haven’t been transmitted globally, except indirectly by dampening investor sentiment. That’s because few global investors are able to invest freely in the A-share market. It’s one of the reasons why volatility in China doesn’t get transmitted the same way as America’s.

“But, if the Chinese market becomes linked to London, then London - and global markets - could be directly affected by the gyrations of Chinese stocks.”

A price worth paying?

As Yueh explains, London has already borne its share of impact from the Chinese market crisis this summer, with a large number of commodity companies listed here having stocks dragged down by China.

Emerald Energy, Specialist Machine Developments and a group of key wind farms, are among British-based interests owned or part-owned by China.

During his visit, Mr Osborne confirmed a £2 billion government guarantee for Chinese investment in the proposed Hinkley Point C nuclear power plant in Somerset, and indicated he expected it to pave the way for further deals.

So is linking stock markets and trading platforms the next logical step?

“It’s a big step and one that the UK may well be keen on to cement a ‘special relationship’ with the world’s second largest economy,” Linda Yueh argues.

“It’s a strategy that makes sense over the longer term, since the special relationship with the US has largely been a fruitful one for Britain.

“But, in the short term, any direct links with China will entail a cost of greater volatility. The UK will need to decide if it’s a price worth paying.”